After seeing the movie "Trading Places" (1983), starring Eddie Murphy and Dan Aykroyd, for the thousandth time during the holiday season, I decided to write a quick post explaining what happened at the end of this movie that gets so many people puzzled (including me for the first couple of times I've seen it).

This entertaining 80-ies comedy can actually teach you more about finance and trading than any other Hollywood movie (not counting documentaries), including the infamous "Wall Street" (1987), starring Michael Douglas as the ruthless Gordon Gecko, and especially the latest Scorsese film "The Wolf of Wall Street" (2013).

Anyway, we all know the story from Trading Places. Dan Aykroyd plays a snobbish investor Louis Winthorpe ("the Third"), while Eddie Murphy plays a street con artist Billy Ray Valentine whose lives get reversed as a result of a bet between two cruel millionaires, the Duke brothers. The Dukes own a commodities brokerage house and have young Winthorpe as their managing director. When they encounter a street hustler/con artist Billy Ray Valentine falsely accused of trying to rob Winthorpe they decide to conduct a social experiment in which they switch the social positions of these to men to determine which is more important: environment or heredity. Winthorpe is framed with drugs and ends up in jail, loosing his fiancee and his social status, while Valentine is being given Winthorpe's job and all possessions, including his house.

![]()

Needless to say, a lot of funny stuff happens on the way, but when Winthorpe and Valentine realize the deceit they want to get back at the Dukes, and the best way of doing so is by bankrupting them. And the best way of doing that is with a little short-selling.

Needless to say, a lot of funny stuff happens on the way, but when Winthorpe and Valentine realize the deceit they want to get back at the Dukes, and the best way of doing so is by bankrupting them. And the best way of doing that is with a little short-selling.

What is short-selling?

Why short-selling, or the cleaner "going short"? Because it's the opposite of the conventional trading practice of "going long" - when an investor expects a price of a stock to rise in order to make a profit.

So how did they do it in Trading Places?

Going back to the movie, the question is how was it possible for Winthorpe and Valentine to make hundreds of millions in one hour on the trading floor, while simultaneously bankrupting Duke and Duke (the final scene)?

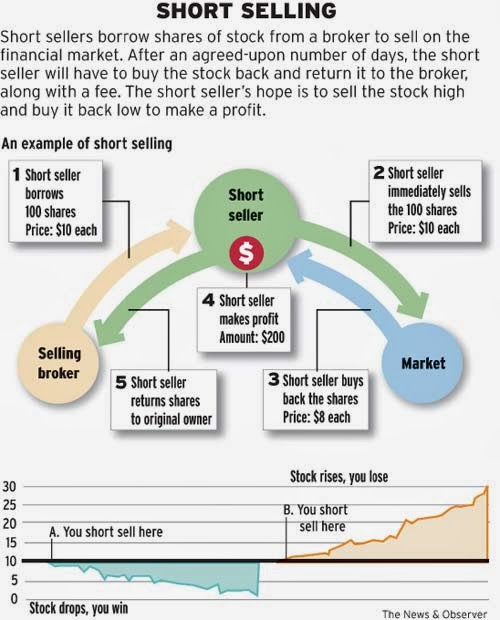

Short-selling is basically the reverse of normal trading. In normal trading you buy low expecting the price of a security to rise in order to make a profit. When short-selling, you expect the prices to drop instead of rise and so you decide to sell high and buy low. It sounds puzzling at first, but it really isn't.

|

| Source: EconMatters |

Short-selling implies selling a security you do not own at a high price, with the obligation to buy it back later at a lower price. If the price drops, you made a profit, since the cost of repurchase of the security will be lower than what you got for it during the initial short sale. The higher the drop in price (high-low spread), the more money a short-seller gets. On the other hand if the price goes up, one can lose a huge amount of money.

The graphic summarizes the whole story pretty well. Usually a short-seller will borrow shares to sell them, thus creating an obligation to return them. He bets against the shares selling them immediately at a high price. If the price goes down, he can make a profit the size of the spread (just like with normal, "long" trading). He waits for the stocks to plummet and then buys back the stocks he pre-sold at a lower price, since he still has an obligation to return these shares. The transaction also includes a fee to the broker who borrowed him the shares. You can do the same thing with futures contracts. Futures are perfect for short-selling: contracts one can sell when he doesn't yet own a commodity (or asset). Making a sell of a 1000 pounds of a commodity (say oranges) at $2 per pound in March simply means that the seller is obliged to provide and the buyer is obliged to purchase the commodity at the specified future time and price (in this case three months from now, at $2 per pound). It doesn't matter how you get the commodity (or whatever you're selling) as long as you are able to provide it at the designated time. That's why the buy back is important - you still have an obligation to provide the stuff, and your buyers have an obligation to pay you at the high price (the agreed $2), even if in the mean time the price dropped to, say 50 cents.

Going back to the movie, the question is how was it possible for Winthorpe and Valentine to make hundreds of millions in one hour on the trading floor, while simultaneously bankrupting Duke and Duke (the final scene)?

The answer: Short-selling. And of course: rigged insider information. This is the most important piece of the puzzle. Short-selling can only be fully efficient if you know the price will go down. Then you can scam everyone else easily.

The insider information I'm referring to is the Dept of Agriculture crop report for oranges (they're trading a commodity - frozen orange juice). The Dukes hired their secret agent Mr Beeks to get them the report before anyone else sees it. Unfortunately for them, Winthorpe and Valentine get their hands on the report before the Dukes do and feed them false information. The Dukes are led to believe that the weather was bad and so the harvest was less than normal. Therefore the Dukes are expecting high prices (low supply + high demand = high prices). However the actual report signals the opposite - the harvest was unaffected by the bad weather, and the supply will be plentiful. Hence the scope for short-selling, as Winthorpe and Valentine know that the price is likely to go down.

Trading floor. The Dukes tell their broker to buy as many frozen concentrated orange juice (F.C.O.J.) contracts as he can before the crop report is revealed to the public. They anticipate prices to rise high after the report is revealed so they are looking to make a good profit.

Trading begins at 102 cents per pound (at 15,000 pounds of F.C.O.J. per contract - size of a typical contract - the value of a single contract is $15,300). Once everyone realizes the Dukes are trying to 'corner the market' (it means getting sufficient control of a stock or commodity so that one can manipulate its price), they all try to get their hands on the contracts, driving the price up (high demand, typical bubble behaviour).

At the same time Winthorpe and Valentine are on the floor but are not selling yet. They have to wait for the price to go really high before they can start pushing it down. Have in mind they need to maximize the high-low price spread.

When the price reaches 142, that's when Winthorpe yells: "Sell [some quantity] in April at 142!" Now they are short-selling (step 1): selling futures contracts they don't hold. Yet. They are betting they will be able to buy the contracts later at a lower price and thus make a profit.

The other brokers are buying from them as they still think the price will go up, since the Dukes are applying the same strategy. However the price is going down. The reason is again simple supply and demand. New, fresh supply of future stocks decreases the prices of the contracts. Trading continues until the crop report is being revealed when everyone pauses to hear it. The price is back down to the initial 102.

The real crop report (read out by the Secretary of Agriculture) states that the harvest was good and that the supply of oranges is plentiful. The over-inflated price starts dropping significantly as everyone starts frantically selling to get rid of their contracts and at least zero their position before trading ends. The Dukes are in disbelief. Their broker is full of soon to be worthless contracts and is literary overcrowded by an army of traders quickly getting rid of their contracts.

When the price falls down to 46, Winthorpe and Valentine announce their second important move (step 2: the buyback): buy at 46! This is the spread they've been waiting for (142-46). They have to buy a lot of these worthless contracts to zero their position. They are basically the only buyers left on the floor. However it is important for them not to buy directly from the Dukes' broker. They want him to hold onto a lot of those contracts he bought at over-inflated prices.

When trading ends, the price is down to 29 cents per pound, and they've managed to deliver on all their short-sold contracts.

How much have they made? Let's see. In the movie Winthorpe says they've moved around 20,000 contracts. Assuming they've sold short at a constant pace from 142 down to 102, and that later they've bought them back while the price was falling from 46 down to 29, let's say that the average sell price was around 122 cents per pound, where the average buy-back price was 37.5 cents per pound. The spread is therefore 122 - 37.5 = 84.5 cents per pound profit. Per single contract this is 15,000 pounds * 84.5 cents per pound = $12,675 per contract. Multiply this by roughly 20,000 contracts and their total profit was: $253,500,000.

In just one hour on the trading floor. Impressive. That's what you can do with just a little bit of favorable insider info.

On the other hand, the Dukes faced a margin call of $394,000,000 (they were left holding even more contracts), rendering them completely broke. Buying shares on margin means you are borrowing money to buy more shares than you have cash for. The Dukes have done this believing they have a sure bet based on their (albeit false) insider info. After a drop in prices, when the value of your asset becomes too low, the exchange announces a margin call, insisting you pay immediately. As they couldn't do this, they were bankrupt.

However, since this is a movie, it suffers from several flaws. This wouldn't be possible to pull off in today's market. Or even in the one in the 80-ies. There are rules and regulations that prevent exactly the sort of thing that happened in the movie. The so-called 'circuit breakers' limit or stop trading when prices go up too high, and especially if they drop down too low. Also, the regulators recently actually came up with the "Eddie Murphy rule" that expanded insider trading laws with regular securities to the futures contract market. The goal was to prevent exactly the sort of insider trading that happened in the movie. This rule is actually a part of the Frank Dodd financial overhaul bill. How's that for a quick reaction from the regulators (27 years!).